Countdown to Crisis: Kingdom Come

You’ll probably be aware by now that three versions of Superman will grace our screens in the Arrowverse’s upcoming uber-crossover Crisis On Infinite Earths. The most recent incarnation, Tyler Hoechlin’s Clark from the current Supergirl series, will be most familiar to viewers, while the second, played by Tom Welling, originated in the young Superman chronicle Smallville, which ran for ten seasons from 2001 to 2011, and which even some of you younger readers are probably aware of even if you’ve not seen all of it. The least known of the trio is played by Brandon Routh, already a part of the Arrowverse as Ray Palmer/The Atom.

Routh never got to play his own version of Superman. Yes, he headlined the 2006 misfire Superman Returns, but that was intended as an imitation of Christopher Reeve from Superman (1978) and Superman II (1980), and a continuation of that specific saga that bypassed the two significantly lesser quality sequels Superman III (1983) and Superman IV: The Quest For Peace (1987). The film’s failure meant he never got to realise his own interpretation of the character, which is now being rectified when he joins a number of Arrowverse actors pulling double duty in Crisis by also playing the Superman from Kingdom Come.

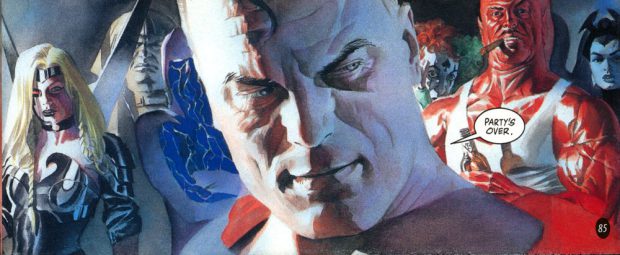

Written by Mark Waid, painted in gauche watercolour by Alex Ross and published under DC’s alt-reality Elseworlds imprint in 1996, Kingdom Come is a four-issue miniseries that begins in a world where Superman has given up. A decade prior to the story’s commencement, the entire staff of The Daily Planet – including Lois Lane – were massacred in a gas attack by the Joker, with the Clown Prince of Crime subsequently being snuffed out by Magog, a violent antihero created for the series to represent everything about contemporary superhero design that Waid disliked. At Magog’s subsequent trial he was acquitted of murder, with public opinion shifting in favour of a less forgiving brand of superheroics and Superman’s ethos of idealism being seen as dated and of little relevance in an increasingly cynical world, a direct dig at the ‘dark and gritty’ direction superhero comics went in the ‘90s. If you weren’t around for that decade, I cannot stress how utterly devoid of subtlety it was.

Written by Mark Waid, painted in gauche watercolour by Alex Ross and published under DC’s alt-reality Elseworlds imprint in 1996, Kingdom Come is a four-issue miniseries that begins in a world where Superman has given up. A decade prior to the story’s commencement, the entire staff of The Daily Planet – including Lois Lane – were massacred in a gas attack by the Joker, with the Clown Prince of Crime subsequently being snuffed out by Magog, a violent antihero created for the series to represent everything about contemporary superhero design that Waid disliked. At Magog’s subsequent trial he was acquitted of murder, with public opinion shifting in favour of a less forgiving brand of superheroics and Superman’s ethos of idealism being seen as dated and of little relevance in an increasingly cynical world, a direct dig at the ‘dark and gritty’ direction superhero comics went in the ‘90s. If you weren’t around for that decade, I cannot stress how utterly devoid of subtlety it was.

After the departure of Kal-El – with the abandonment of his responsibilities he also left behind his civilian identity – most of the other first generation superheroes followed suit, realising that humanity had moved on without them, leaving the world as a battleground between more reckless heroes and villains, ones who fight not out of any great desire to make a mark or achieve anything, but purely for the thrill of combat itself, and done so without any thought given to the civilians who get caught in the crossfire.

Spending the intervening years isolated within the Fortress of Solitude in a holographic recreation of his childhood farm, he hides from the world until he is spurred back into action by Wonder Woman after Magog leads the “Justice Battalion” in a battle against the life-absorbing villain Parasite, in which Captain Atom is killed and the resultant radioactive fallout kills millions and turns the Midwest into an irradiated wasteland.

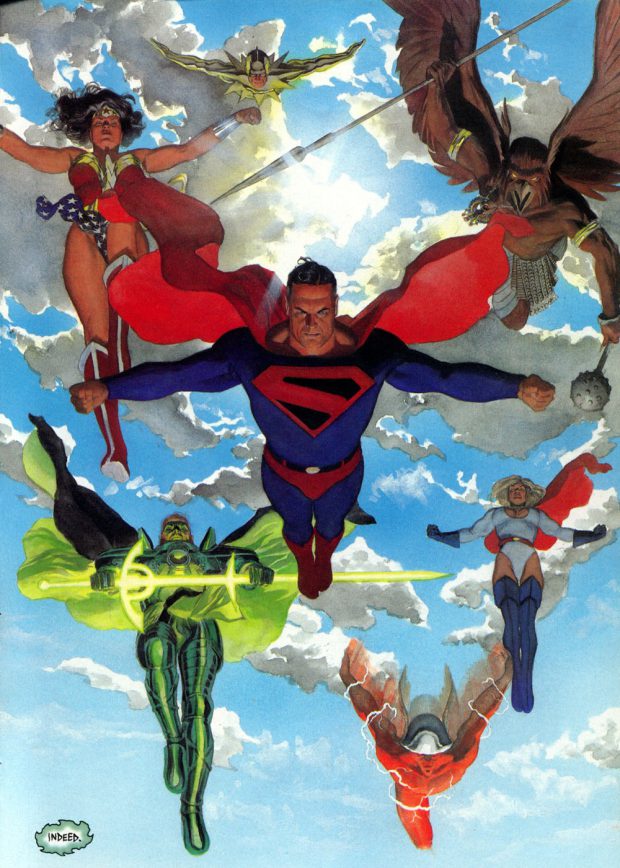

Superman reforms the Justice League and pulls its ageing former members from their own self-imposed isolation – the Flash relentlessly patrols Keystone City in a blur of red lightning; Hawkman rules the Pacific Northwest and violently rejects the interloping of any humans into his environmental sanctuary; Green Lantern sits in an orbital fortress of his own creation in vigilance against extraterrestrial threats that never materialise; Batman controls Gotham with an army of black steel automata – and the group returns to reshape the world more to their liking. However, advancing age has robbed the former heroes of patience, so instead of a band of superheroes swooping in to save the day, they act like a unit of soldiers facing an enemy, a choir of angelic warriors descending from on high to deliver the word of the new world order, and that message is fall in line or get out of the way.

Superman reforms the Justice League and pulls its ageing former members from their own self-imposed isolation – the Flash relentlessly patrols Keystone City in a blur of red lightning; Hawkman rules the Pacific Northwest and violently rejects the interloping of any humans into his environmental sanctuary; Green Lantern sits in an orbital fortress of his own creation in vigilance against extraterrestrial threats that never materialise; Batman controls Gotham with an army of black steel automata – and the group returns to reshape the world more to their liking. However, advancing age has robbed the former heroes of patience, so instead of a band of superheroes swooping in to save the day, they act like a unit of soldiers facing an enemy, a choir of angelic warriors descending from on high to deliver the word of the new world order, and that message is fall in line or get out of the way.

This Superman is still recognisable as the Big Blue Boy Scout, but is also Superman the warrior, the one who has battled entities from a hundred worlds. Instead of the compassionate and forgiving superhero, the black background of his suit’s emblem reflects the darkness that is now a part of him. In comparison to the unforgiving nature some of his contemporaries begin to display he comes off as idealistic, but also someone his mainstream continuity counterpart would barely recognise as the same person, as the intensity of his experiences have hardened him against the forgiving nature with which readers and viewers will be more familiar. He turns into a fascist dictator, rounding up metahuman dissidents and imprisoning them in a “re-education” prison, setting the scene for a battle between a trio of groups vying for control, each of whom believe that theirs is the right to dictate how the world should be.

In spite of the magnitude of events, the narrative device is one of observation. The story is framed through the perception of Norman McCay, a pastor barely able to convince himself of the importance of the teachings he preaches, never mind his congregation. After being gifted (or possibly cursed) with apocalyptic dreams by a dying Sandman (Wesley Dodds, not Morpheus), he is visited by cosmic entity of vengeance the Spectre, who has come to stand in judgement on the looming Armageddon.

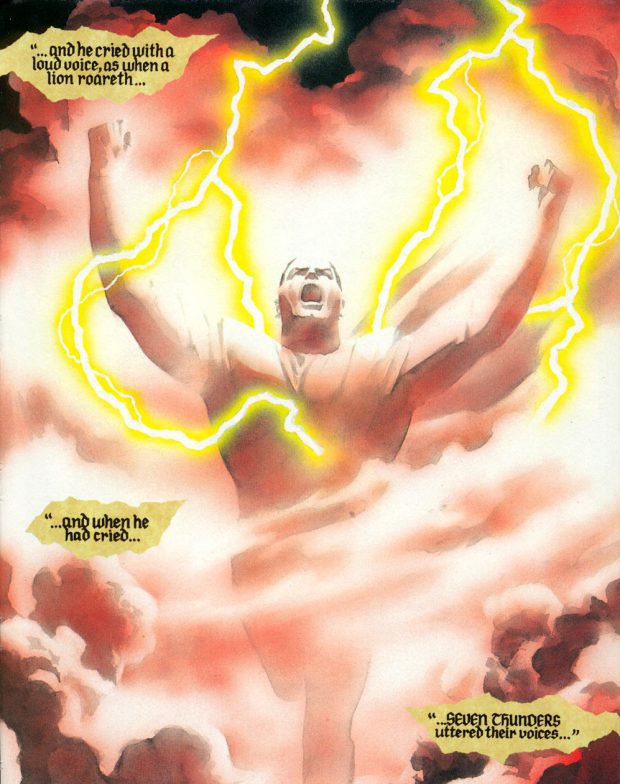

Superman is often portrayed as a Christ allegory, having been sent to become a saviour of humanity and a guiding light by which our highest achievements can be realised. Right from its very title, Kingdom Come is a story awash with that same metaphor, but instead of the compassionate saviour of the Gospels, this one is the harsh and portentous one seen in the Book of Revelation, the story’s biblical imagery and apocalyptic narration transforming the comic a Bronze Age retelling of the End of Days. The re-emergence of Superman from his self-imposed exile acts as a parallel with the second coming of Jesus, while Norman and the Spectre, standing to the side and observing events as they play out, act as the biblical Witnesses.

Superman is often portrayed as a Christ allegory, having been sent to become a saviour of humanity and a guiding light by which our highest achievements can be realised. Right from its very title, Kingdom Come is a story awash with that same metaphor, but instead of the compassionate saviour of the Gospels, this one is the harsh and portentous one seen in the Book of Revelation, the story’s biblical imagery and apocalyptic narration transforming the comic a Bronze Age retelling of the End of Days. The re-emergence of Superman from his self-imposed exile acts as a parallel with the second coming of Jesus, while Norman and the Spectre, standing to the side and observing events as they play out, act as the biblical Witnesses.

It’s not clear from when in the timeline this Superman will be taken to participate in Crisis On Infinite Earths, but the decade of self-imposed exile affords plenty of opportunity to participate in a battle of clashing realities without his absence being noticed by the rest of the world.

Although Crisis will be far from the first instance of an Arrowverse actor playing more than one character, far more common is them simply playing different versions of the same person, such as the endless iterations of Harrison Wells in The Flash, the Black Canary and Black Siren of Arrow, or the heroes’ Nazi counterparts seen in 2017 crossover Crisis On Earth-X. With Ray now often acting as a comic relief character on Legends of Tomorrow it’s quite possible that only he will notice a similarity between his own appearance and that of the ageing Kryptonian, who may well be portrayed as distinguished and handsome, while others are just as dismissive of Ray’s looks in comparison.

With the Kal-El of Kingdom Come being older, more cynical and far less forgiving than the character is typically known for, he will likely act as a counter to the optimism of Supergirl’s Superman and the experienced but still compassionate one of Smallville. One thing that you can be sure of: he won’t just be a similar version of a familiar character there to make up the numbers.